In a 2023 Wall Street Journal article, Henry Kissinger and two collaborators argue that artificial intelligence will disrupt our world at a level not seen since the printing press.1Kissinger, Schmidt, Huttenlocher, “ChatGPT Heralds an Intellectual Revolution: Generative artificial intelligence presents a philosophical and practical challenge on a scale not experienced since the start of the Enlightenment,” The Wall St. Journal, Feb. 24, 2023. That new technology appeared in the mid-1400s, redirected the Renaissance, and enabled the Enlightenment. It also played a central role in overturning the medieval political and religious order, which triggered 150 years of devastating war. Kissinger and co. join a chorus of commentators comparing artificial intelligence to general purpose technologies (though only a few use that vocabulary).2See, Eloundou, Manning, Mishkin, Rock, “GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models,” v. 4 Cornell University working paper (Mar. 23, 2023); N. Crafts, “Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology: an historical perspective,” 37 Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Number 3, pp. 521-536 (2021). Economists and historians use that term for technology that alters an entire economy. The history of these general purpose technologies offers guidance as we predict and prepare for AI’s rewards and its inevitable turbulence.

Artificial intelligence meets the age of the printing press: AI-generated image combining Renaissance and futuristic images

This is the first of three short posts in a series on the history of general purpose technologies — and on what they tell us about our future in a world shaped by AI.

Artificial Intelligence as a General Purpose Technology

Scholars list three requirements for a general purpose technology — for a GPT (not to be confused with generative pre-trained transformers, like ChatGPT: a type of AI with the same initials). A GPT:

- improves over time;

- leads to complementary innovations; and

- spreads across the entire economy, impacting most sectors.

Artificial intelligence almost certainly qualifies. It (1) has improved over time on a long list of metrics and will probably continue. Model complexity, for example, refers to the number of variables a system analyzes to make predictions. That figure rose more than 100x between 2019 and 2021 for certain systems. Or to take a better-known (and related) example, chatbots recently improved from systems that answer only targeted, relevant questions to large language models, like ChatGPT, which “talk” to us on any topic. Artificial intelligence has also (2) led to complementary innovations. Those include AI-driven robots, legal research software, and facial recognition systems. And while artificial intelligence has not yet (3) spread across the entire economy, it’s hard to imagine many industries that won’t eventually take advantage of it.3For a brief summary of artificial intelligence progress, see, “The state of AI in 2022—and a half decade in review,” McKinsey & Co (Dec. 6, 2022).

A late-Medieval GPT: three-masted ships (Portuguese carracks)

Opinions differ on what else qualifies as a general purpose technology. Historians and economists have pointed to pottery, farming (agriculture), metal smelting, the wheel, writing, bronze production, iron production, the water wheel, three-masted ships, the printing press, steam power, railways, electric power, cars, and information technology, among others. (The last of those, IT, includes artificial intelligence. But most authorities treat the two as separate: earlier and later waves of computer tech.) Each GPT expanded the economy. But some reshaped the world more than others.

1. Recent General Purpose Technologies: Steam, Electricity, and Information Technology

Economists point to three classic GPTs: steam power, electric power, and IT. None triggered the violence and revolution surrounding the printing press. But all three expanded and reshaped the economy, destroyed and created jobs, and altered daily life.

The Pace of Change

James Watt patented the steam engine in 1769. It had relatively little economic impact, however, until the 1830s, even in its home country, Great Britain. And steam didn’t spread much beyond textile factories, metal manufacturing, and coal mines until the 1870s. So we can measure the pace of change in decades. Electricity and IT changed the world slightly faster but still on a scale of decades, not years.4Crafts, “Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology,” p. 524.

If artificial intelligence moves at the same pace, we should have plenty of time to prepare and adjust. But does technology advance faster in the 21st century? And will AI’s power to improve itself drive even faster change? Maybe, but maybe not. No matter how fast artificial intelligence improves, businesses and governments cannot snap their fingers and adopt it. They have to build and install AI-based computer systems: a slow and expensive process.

Employment

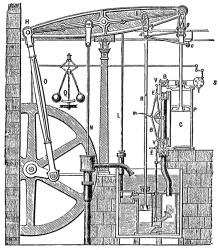

Diagram of a 1784 Watt steam engine

Steam power launched the First Industrial Revolution in Britain. For years, economists have argued that industrialization reduced British laborers’ relative wealth and quality of life. Steam destroyed working class jobs by replacing their products with factory-made goods, which demanded less labor. Steam-powered textile mills, for instance, essentially eliminated Britain’s hand-weavers by the late 1800s. Other working class jobs disappeared too — and many laborers found themselves in factory jobs with low wages.

A more recent line of thinking, however, paints a brighter picture. Close analysis of the economic data suggests laborers’ average buying power increased during the 1800s. And the working class share of national income held steady, even as the national pie got bigger.5Crafts, “Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology,” p. 528-529. In other words, laborers got slightly richer (or less poor). That’s probably because the Industrial Revolution replaced as many jobs as it destroyed. It created new positions like boilermakers, mechanics, and floor supervisors, among many others. And it increased demand for metalsmiths, coalminers, and other existing workers.

Electricity and IT followed similar patterns, creating at least as many jobs as they destroyed. In fact, about 60% of today’s U.S. jobs did not exist in 1940.6See, “Your job is (probably) safe from artificial intelligence,” The Economist, May 7, 2023. See also, Crafts,” Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology.”

In each case, some people who lost jobs did not recover. They never got one of the new jobs created by the GPT. But overall, steam power, electricity, and IT added jobs. If artificial intelligence follows the same pattern, we could be looking at a rosy future, though not for everyone.

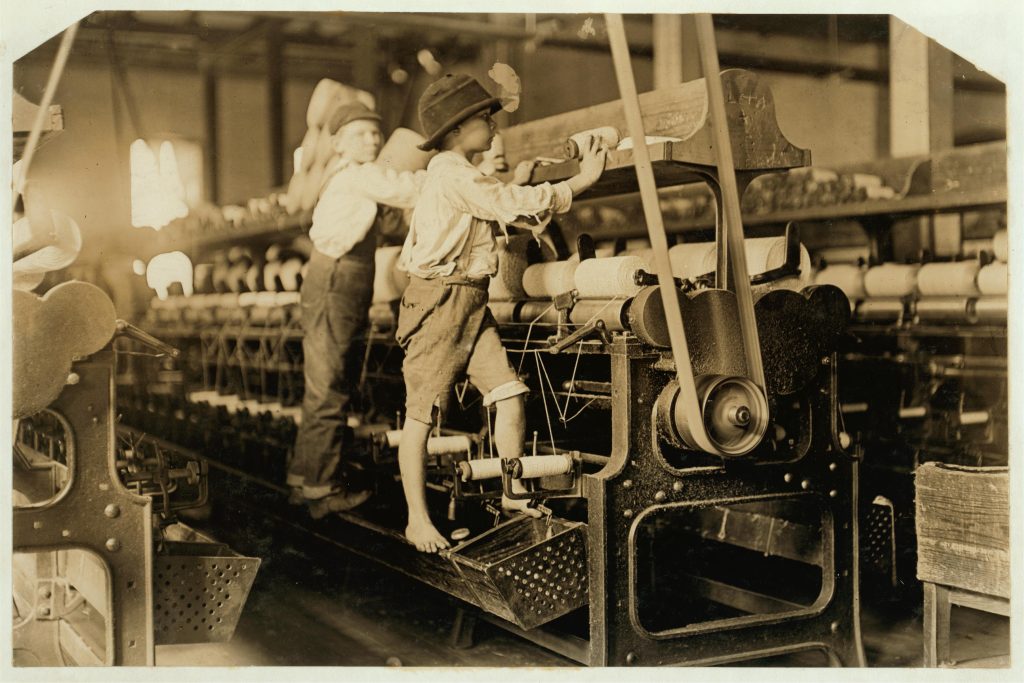

Workplace Horrors

Steam power and the broader First Industrial Revolution also created truly horrible workplaces. Think of the grim, dangerous Dickensian factories of the early 1800s, with their twelve-hour workdays and, in some cases, child laborers. That problem did not end on its own. Parliament stepped in repeatedly during the 1800s, with restrictions on child labor and laws requiring improvements like safety standards and shorter workweeks.

A dark side of the Industrial Revolution: child labor and unsafe working conditions

Fortunately, that sort of government intervention spread to other nations — and lasted. Workplace safety, overtime, and child labor laws still protect workers, as do minimum wages, union organizing rights, and other systems. Probably as a result, electricity and IT did not mimic the early horrors of steam. That bodes well for AI.

Social and Political Disruption

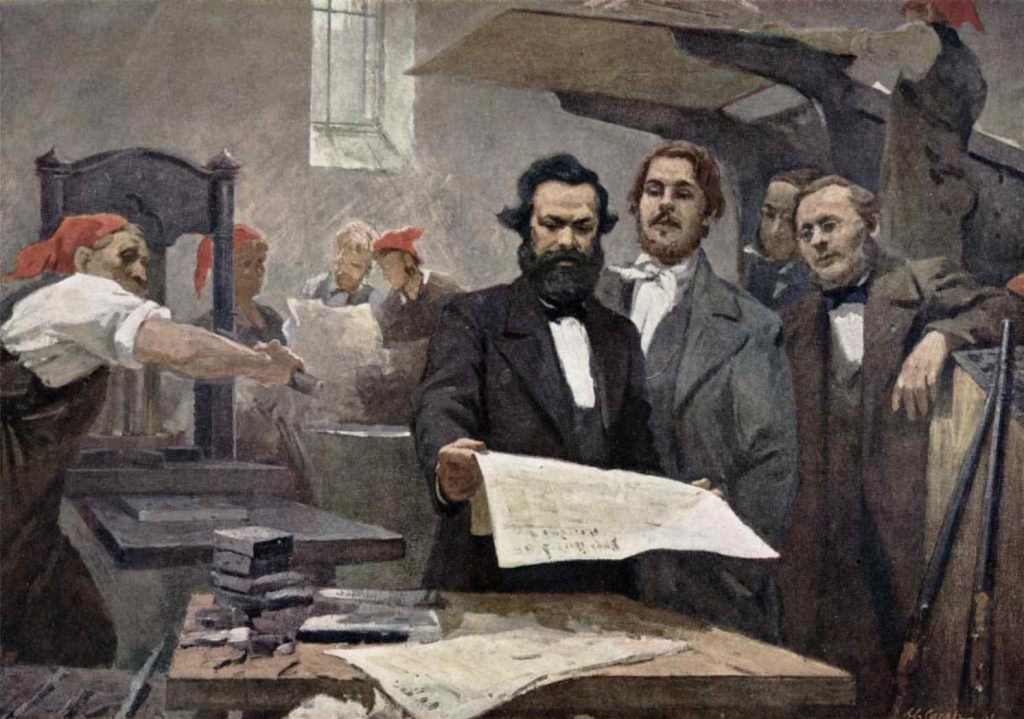

Steam power and the First Industrial Revolution did not rapidly overturn the British social/political order, but they did transform it. Landowning aristocrats lost power during the 1800s as industrialists surpassed their wealth. And the middle class grew in numbers and power, including as “white collar workers” managing the new industries. The era also gave birth to a new class of laborers: urban industrial workers. The First Industrial Revolution spurred new economic and political movements too, particularly unions but also communism and socialism. The latter two tried to seize control in the U.K. and other industrial nations but failed.

Marx and Engels, political philosophers of the Industrial Revolution, meet the printing press. Karl Marx predicted communist revolutions in the U.K., U.S., Germany, and other industrialized nations. But he did not anticipate the rise in the proletariat’s living standards, and his ideas didn’t take hold among those nations’ workers.

The age of steam and industrial revolution also witnessed very little war for Great Britain. A general peace held across Europe, with only short interruptions, from the 1815 defeat of Napoleon to the 1914 start of World War I.

Steam and industry reshaped the U.S. and other nations in similar ways. The 1800s did witness revolutions in France and elsewhere, but it’s hard to pin the blame — or credit — on steam power. (The printing press may deserve more blame/credit, as we’ll see in the next post.) Overall, steam brought unprecedented change but not revolution. The same goes for electricity and IT.

If only AI had been available to staff those awful Victorian factories

If artificial intelligence fits this GPT pattern, history suggests it will change the social order but not so quickly that we end up killing each other … much.

Broad Strokes

AI differs from these earlier GPTs in one crucial respect. Steam and electricity destroyed blue collar jobs, and to some extent so did IT. Artificial intelligence will probably impact white collar jobs most — e.g., programmers, accountants, lawyers, office workers. History tells us angry lawyers and other out-of-work elites foment revolution. However, educated workers often accept retraining relatively easily. And many have savings to support them through job transitions. So the white collar factor gives us little clear guidance.

Of course, one could argue that steam power, electricity, and IT changed our world more than any GPT since farming. We now live in an industrial society vastly different from the agriculture-dominated world of the past 10,000 years. However, none of these three GPTs alone gets credit for that transformation. Nor do the three together. The Industrial Revolutions of the past two centuries relied on a long list of additional GPTs: chemical technology, oil, automobiles, and more.

Click here to read the next post in this series, which looks at a more revolutionary GPT: the printing press.

© 2023 by David W. Tollen. All rights reserved.

Images

- Artificial intelligence meets the age of the printing press, David W. Tollen, NightCafe, 2023

- Portuguese Carracks off a Rocky Coast, anonymous, c. 1540 — edited for brightness and cropped

- Sketch showing a steam engine designed by Boulton & Watt, England, 1784

- The dark side of steam power, Children’s Bureau Centennial, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

- Marx and Engels at the Rheinische Zeitung, E. Capiro, 1849

- If only AI had been available to staff those awful Victorian factories, David W. Tollen, NightCafe, 2023

- 1Kissinger, Schmidt, Huttenlocher, “ChatGPT Heralds an Intellectual Revolution: Generative artificial intelligence presents a philosophical and practical challenge on a scale not experienced since the start of the Enlightenment,” The Wall St. Journal, Feb. 24, 2023.

- 2See, Eloundou, Manning, Mishkin, Rock, “GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models,” v. 4 Cornell University working paper (Mar. 23, 2023); N. Crafts, “Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology: an historical perspective,” 37 Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Number 3, pp. 521-536 (2021).

- 3For a brief summary of artificial intelligence progress, see, “The state of AI in 2022—and a half decade in review,” McKinsey & Co (Dec. 6, 2022).

- 4Crafts, “Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology,” p. 524.

- 5Crafts, “Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology,” p. 528-529.

- 6See, “Your job is (probably) safe from artificial intelligence,” The Economist, May 7, 2023. See also, Crafts,” Artificial intelligence as a general-purpose technology.”

Little war for GB in Europe, but did early lead in steam power and IR provide a technological advantage that helped make Britain the largest overseas empire of the time? Perhaps AI could lead to something similar for whoever gets their first.

John, that’s a good questions, but I think it has a complex answer. I think the #1 factor that made GB great was nationalism. They were the first to experience true nationalism and enjoy its many benefits (and pay its costs). That doesn’t mean steam played no role. It’s fair to ask whether the scientific, capitalistic, and generally competitive drives of nationalism led to steam — and steam further boosted British power. I suspect the answer is “yes.” (For more on this, see works by Prof. Liah Greenfeld at B.U.: https://www.bu.edu/sociology/profile/liah-greenfeld/.)